Stacking the Deck for a Resilient Community

Melissa Dean, Ph.D.

Research Fellow, Urban Renewal Center

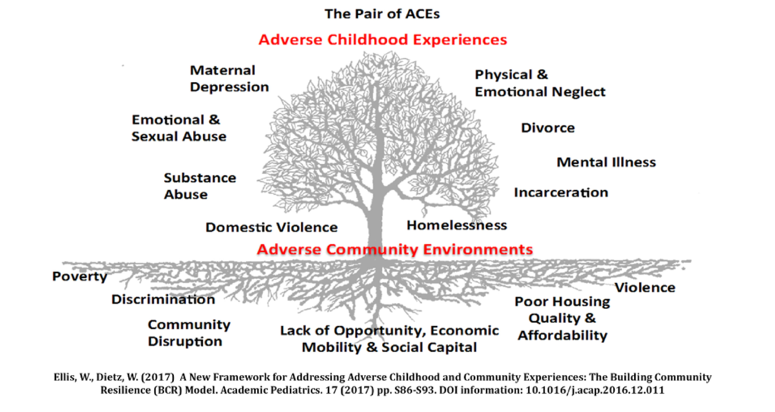

Being dealt a pair of aces is stroke of luck at the card table, but for a community trying to thrive in extremely challenging times, they are another matter entirely. Researchers have identified two sets of ACEs: 1) Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) or categories of abuse, neglect, or dysfunction that correlate with poor health outcomes and 2) Adverse Community Environments (ACEs) produced by structural racism. In combination, this pair of ACEs stacks the deck against community resilience.

Felitti et al. (1998) identified ten categories of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): emotional abuse (recurrent), physical abuse (recurrent), sexual abuse (contact), physical neglect, emotional neglect, substance abuse in the household, mental illness in the household, mother treated violently, divorce or parental separation, and criminal behavior in household. Further studies have validated the original findings and made it “clear that adverse childhood experiences in and of themselves are a risk factor for many of the most common and serious diseases in the United States (and worldwide), regardless of income or race or access to care” (Harris, 2018, p. 39).

Structural racism drives the existence of Adverse Community Environments (ACEs), creating a “pair of aces” that “produce complex trauma felt at the individual, family, and population levels” (Ellis et al., 2022). The second ACEs in the pair include: poverty; discrimination; community disruption; lack of opportunity, economic mobility & social capital; poor housing quality & affordability; and violence (Ellis et al., 2022).

George Washington University’s Department of Public Health has created a visual depiction of this phenomenon called “The Pair of ACEs Tree.” This visual depicts the Adverse Childhood Experiences as branches of the tree whose leaves represent the symptoms that result in chronic illnesses caused by chronic stress. The Adverse Community Environments are depicted as the poor soil in which the roots of the tree must try to grow.

Examining the temperature of a community in each of these areas can assist in assessing its overall health as well as identifying areas to target in mediating the effects of the pair of ACES on individuals, families, and the community as a whole. This article introduces a series of pieces the URC will produce in an attempt to do that for the city of Norfoik and the surrounding communities of the 757.

Ellis et al. (2022) defined community resilience as “(1) the sustained ability of community systems to prepare for, withstand, and recover from acute shocks while addressing and preventing the chronic adverse effects of structural racism, and (2) a community’s ability to cope, strive, and be supported through equitable access to buffers that address and relieve sources of chronic stress and acute adversity” (p. 19). They created a model of community resilience that provides a framework for monitoring and evaluating practices and leading initiatives across multiple sectors in order to address upstream determinants of health (the first pair of ACEs) that result from systemic inequities that are often rooted in racism (the second pair of ACEs).

Addressing the pair of ACEs affecting individuals and communities requires awareness, identification, and collaboration. Awareness of ACEs is critical for every individual in a community because their effects are not limited to the person or group with the adverse experience or condition. One young woman shared her emotional reaction to hearing a presentation on the data surrounding ACE screening: “…I understand now why I am this way. I understand why my siblings are this way. I understand why my mother raised us the way she did. I understand that I can break this cycle of my children and I understand that I’m not a victim, I’m a survivor” (Harris, 2018, p. 178). Everyone is touched by ACEs in some way and needs to know what they are and why they matter. Identification of ACEs through screening needs to occur in a variety of contexts—including medical, educational, and therapeutic. The National Crittenton Foundation made ACEs the core of their work and its “ACE-informed approach to breaking intergenerational cycles of poverty, poor outcomes and violence [yielded] powerful results” (Harris, 2018, p. 176). Finally, collaboration must occur between the many institutions—medical, educational, spiritual, governmental, recreational, therapeutic, social, etc.—that operate within communities in order to heal individuals and communities. As Harris (2018) summarized

…while ACEs might be a health crisis with a medical problem at its root, its effects ripple out far beyond our biology. Toxic stress affects how we learn, how we parent, how we react at home and at work, and what we create in our communities. It affects our children, our earning potential, and the very ideas we have about what we’re capable of. What starts out in the wiring of one brain cell to another ultimately affects all of the cells of our society, from our families to our schools to our workplaces to our jails. (p. 188)

The Crittenton Foundation implored that “[w]e must redouble our efforts to educate communities and systems about the impact of childhood adversity and the toxic stress high exposure creates, as well as, the urgent need for appropriate gender and culturally-responsive approaches to supporting individuals healing from complex trauma.” The URC’s Research and Education Division hopes to be a funnel through which information on each component of this pair of ACEs can be disseminated and discussed in Hampton Roads. To effect change, the conversation must include all concerned parties, which is every individual who lives and works in the 757. It must include parents, young people, educators, clergy, health care professionals, law enforcement, government officials, and every citizen who wants to live in a resilient community in which healthy individuals can grow and thrive.

We cannot afford to sit back and accept the cards dealt us by the current culture of violence, poverty, and inequity. Instead, we need to stack the deck for a resilient community with information, conversation, collaboration, and action between every member of the public in order to awaken our specific society to its promised wholeness and build the beloved community.

References:

Harris, N.B. (2018). The deepest well. Mariner.

See in-text links for additional articles and websites that were referenced in this article.