March 20, 2020

by Alexander Fella | office@theurcnorfolk.com

For the first time we are bringing material from archives across the country together with a narrative timeline to look at Norfolk, Virginia’s history of school segregation. Below you will find primary sources, photographs, videos, and documents detailing the long history of segregated education in Norfolk, and the ardent efforts by those who fought against injustice.

Segregation A History of Norolk Schools

Margaret Crittendon Douglass Arrested for Educating Black School Children.

Margaret Crittendon Douglass ca. 1850

Norfolk police surrounded the house of Margaret Crittendon Douglass. Inside was Margaret’s daughter Hannah Rosa and twenty-five black school children. The police raided Douglass’ home, and closed Douglass’ school. Douglass, a defender of slavery, was sentenced to one month in prison for violating Virginia's 1847 Criminal Code: “Any white person who shall assemble with slaves, [or] free negroes...for the purpose of instructing them to read or write,...shall be punished by confinement in the jail...and by fine...”

Norfolk Annexes First Black Public High School

J. T. West High School

J. T. West High School

Norfolk annexes Huntersville, and with it the old Barboursville School, renaming it J. T. West High School. West High School became the first public high school for African Americans in Norfolk, graduating its first class in 1914. West High School did not have indoor plumbing until the 1930s.

Norfolk Builds Matthew Fontaine Maury High School

Virginian-Pilot Article from 1911 detailing the opening of Maury High School.

Norfolk opens Maury High School in 1911. The white-only school included in-door bathrooms, marble floors, a library, an auditorium, and a cafeteria.

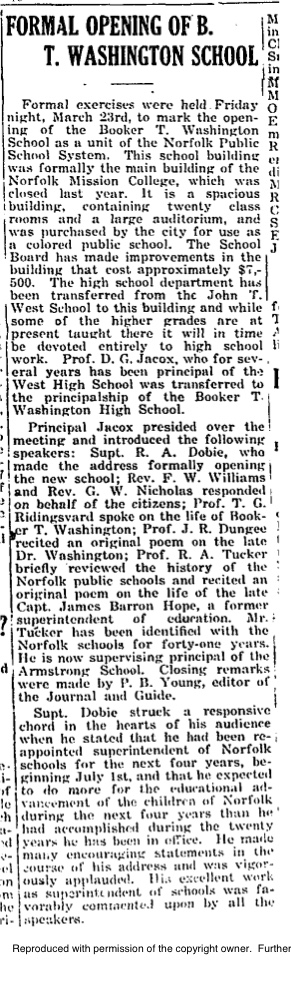

Norfolk Opens Booker T. Washington High School

New Journal and Guide reporting about the opening of Booker T. Washington High School, then an all-black school.

In order to relieve overcrowding of black high school students from West High School, Norfolk acquires the old Norfolk Mission College, renovating the site and reopening the school as Booker T. Washington High School.

Urban Boosterism brings "Hand-Me-Down" Schooling.

During the 1920s and 1930s, new trolly cars began carrying white families to new affluent suburbs in Ocean View, Larchmont, Edgewater, and Ghent. As white families moved away, Norfolk began converting previously all-white schools into black schools in a process known as "hand-me-down" schooling, keeping schools segregated without having to build new schools specifically for African Americans. Including Henry Clay Elementary School which was converted into the Laura E. Titus Elementary school for black students.

Throughout the early 20th century, many white families in Norfolk moved out of downtown Norfolk into white-only suburbs further away. This concentrated black poverty in Norfolk slums, which were called “the worst in the country.”

See what the difference between a black neighborhood and a white neighborhood looked like in the 20’s and 30’s

Norfolk Slums on the Kent & Jefferson Street, Undated (NRHA)

White-Only Holland Apartments on Mowbray Arch in Ghent, ca. 1925 (Norfolk Public Library)

White-Only Park Manor Apartment on Granby Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, ca. 1929 (Norfolk Public Library)

Slum Housing in Norfolk, Undated (NRHA)

Sylvan Altschul Residence in Meadowbrook, ca. 1930 (Norfolk Public Library)

Slum Housing in Tidewater Gardens, Undated (NRHA)

White-only Larchmont Village construction, ca. 1938 (Norfolk Public Library)

Slum Housing in Norfolk, Undated (NRHA)

Norfolk begins "Project One."

The Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority kicks off its post-war slum clearance projects with the demolition of slums in today's Tidewater Gardens. In its place, the NRHA built public housing and surrounding roadways to act as barriers to keep Norfolk's African Americans geographically concentrated in poverty.

16 Year Old Barbara Johns Organizes Walkout at Moton High.

Barbara Rose Johns

Barbara Rose Johns

At Moton High School in Farmville, Virginia, 450 students were enrolled at a school built for 180. Moton had no gym, no lunchroom, and no indoor plumbing. "Classes were held in farm buildings and chicken houses...Students had to hold umbrellas when it rained because the roof leaked so badly." On the other side of town, the all-white Farmville High School had modern facilities that excluded black students. Barbara Johns, then a sophomore at Moton, organized a school-wide strike, marching to the homes of School Board members to ask for better educational facilities. When they refused, Johnson and 450 students remained on strike. A month later, the NAACP filed a suit on Johns' behalf, which became Dorothy E. Davis et al v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, one of the five cases folded into Brown v. Board of Education.

See what Farmville’s all-black school looked like compared to Farmville’s all-white school

Black-Only Robert Russa Moton High School

Moton High Classroom (National Archives)

Moton High Auditorium (National Archives)

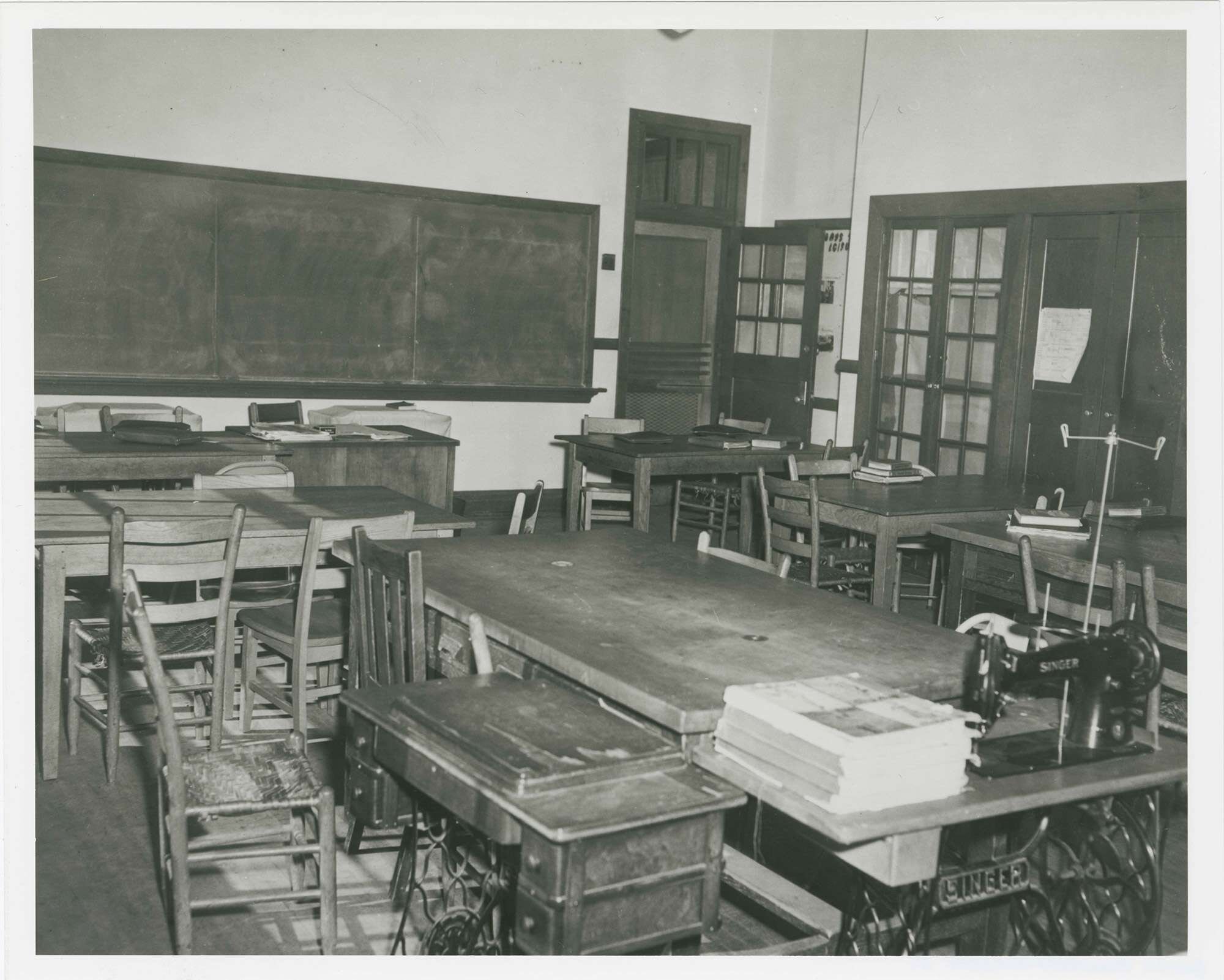

Moton High Home Economics Classroom

White-Only Farmville High School.

Farmville High Classroom (National Archives)

Farmville High Auditorium (National Archives)

Farmville High Home Economics Classroom

Supreme Court decides Brown V. Board of Education.

Watch Thurgood Marshall's reaction to Brown ruling (NBC/Universal, 1954)

The Supreme Court rules school segregation illegal, overturning Plessy v. Ferguson and with it federal laws protecting "separate but equal," schools.

"Massive Resistance" Begins in Virginia

New Journal & Guide report on Virginia legislator dissent following Brown.

New Journal & Guide report on Virginia legislator dissent following Brown.

Following Brown Virginia Governor Thomas B. Stanley convenes a nearly-all-white commission to plan Virginia's defense against school integration in what became known as the Gray Commission. The first step in Virginia's plan of 'Massive Resistance' was to stall on school integration.

Brown v. Board II Issused

As States across America stalled on integrating their schools, the Supreme Court issued a second opinion on the original Brown case, which remanded all future school segregation cases to the lower courts, effectively limiting the possibility for states to tie-up school desegregation in the high court. It also issued firm instruction to States to act "with all deliberate speed," on the matter of desegregating their schools.

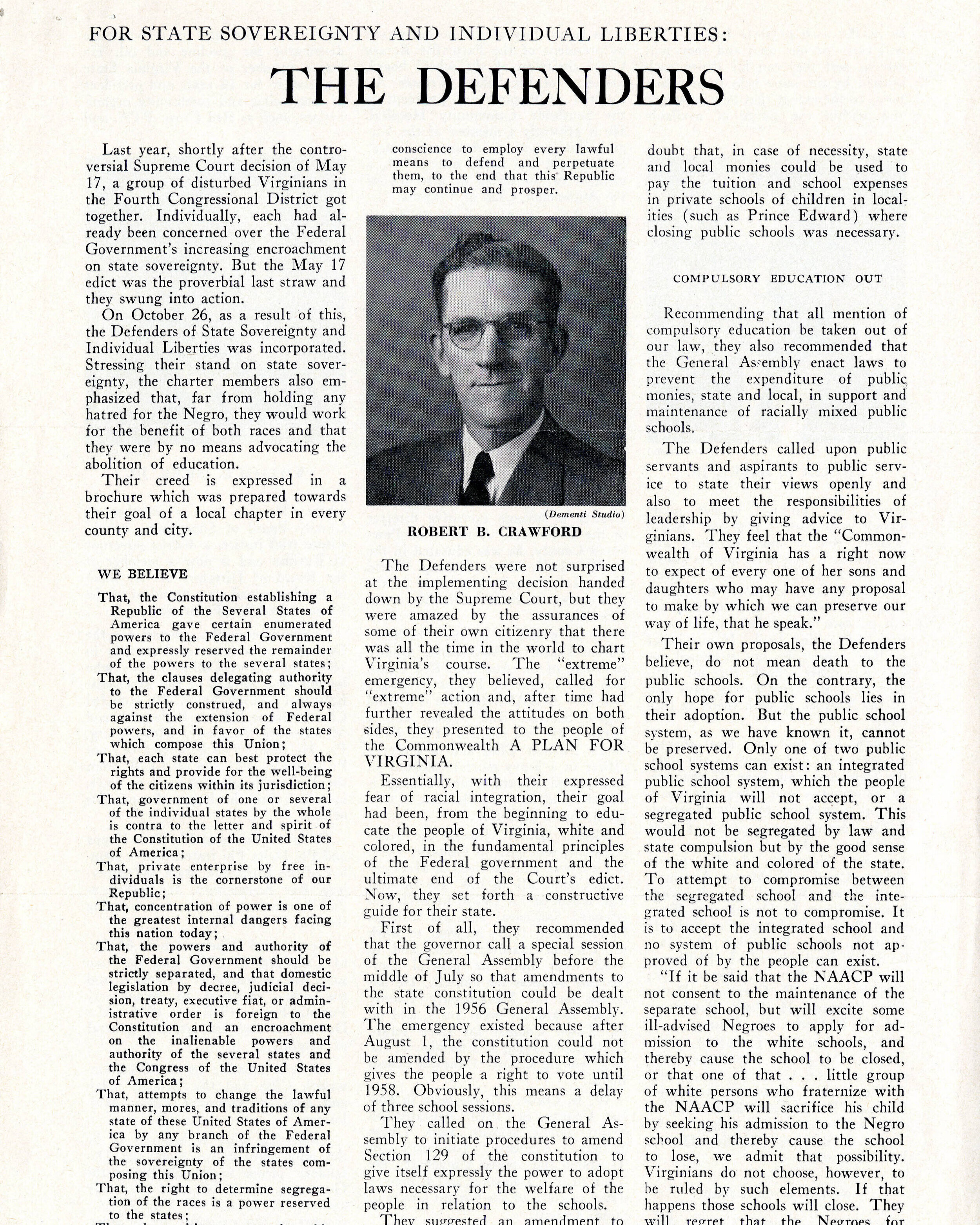

'The Defenders' Issue Plan Against Integration

Pamphlet from 'The Defenders', a Virginia citizen council against desegregation. (Old Dominion University Archives)

The Defenders, a local group organized around school desegregation, begins issuing policy recommendation to state lawmakers, gathering support in Norfolk and from U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd

Explore the anti-integration propaganda that emerged in Virginia following Brown and Brown II

Defenders’ Pamphlet Opposing Desegregation.

(Old Dominion University)

Southern Presbyterian Pamphlet protesting “unnatural” integration.

(Old Dominion University)

Gray Commission Issues Findings to Gov. Stanley; calls for referendum

Senator Garland Gray, a loyalist to Senator Harry F. Byrd issues the findings of his commission to Gov. Stanley, making recommendations for Virginia's plan of Massive Resistance to keep school segregated. Sen. Byrd immediately calls a state-wide referendum to amend Virginia's constitution.

The Gray Commission became a cornerstone in Virginia’s plan of Massive Resistance. Notably, the commission made three recommendations: One, that the Virginia School Board change their pupil assignment plan so as to keep schools segregated. Two, an amendment to Virginia's compulsory attendance law, so as not to force students to attend integrated schools.

Going even further, the Commission recommended the State either de-fund or outright close public schools that integrated. And most importantly, the Commission requested that the School Board allot state funds for vouchers to send white children to private schools. However, in order for Virginia to provide tuition grants to white students, Virginia needed to hold a state-wide referendum to amend their constitution, specifically to amend §141 of the Virginia Constitution, which barred the use of public funds for private schools.

The impending referendum on January 9th, 1956 brought with it a federal campaign and a hard political fight for those seeking to fulfill Brown v. Board's mandate. Below are some of the materials produced leading up to the vote, as well as interviews with Gov. Stanley and the Gray Commission report itself. Click on any of the images to enlarge them.

See the State’s Campaign Poster On The Referendum

Read: Virginia’s Board of Education Support for Segregated Schools

Read: The National Education Association’s Bulletin on Virginia’s Referendum

Read the full report from the Gray Commission

Read: The Q&A Pamphlet from the State Referendum Information Center

Read Legislator Robert Button’s Pro-Referendum Speech to Virginia Lawmakers

Watch: Virginia Gov. Stanley Interviewed about repealing Section 141 to give White students grants.

Virginia Votes to Repeal §141 of the Constitution.

The referendum to amend Section 141 of Virginia's constitution passes on a nearly four to one margin, granting state-wide financial assistance to white students to attend private schools.

Sen. Byrd delivers his "Southern Manifesto" to the Senate.

Sen. Harry F. Byrd, (Virginia History Museum)

The "Southern Manifesto", written between February and March is signed in congress by 82 representatives and 19 senators, including Byrd. The manifesto declared an "abuse of power" by the Supreme Court, and vowed that legislators would use all available means to resistance forced school desegregation.

Governor Stanley Announces "Massive Resistance" Laws to Take Effect.

Gov. Stanley issues a statement giving himself a new set of anti-desegregation powers, in what will become known as the "Stanley Plan." Included in Stanley's plan is the power to close any school that is facing orders to desegregate, as well as cutting public funds to desegregated schools.

See The Press Reaction to Gov. Stanley’s Announcement of New “Massive Resistance” Laws

Read the New Journal and Guide’s Reaction to Gov. Stanley’s Plan.

Political Cartoon from Norfolk’s New Journal and Guide protesting Massive Resistance

Read the Roanoke Times Editorial Reaction to Gov. Stanley’s Plan

Read the Richmond Times-Dispatch Reaction to Gov. Stanley’s Plan

Judge Strikes Down Norfolk's "Pupil Placement Plan."