Flooding By The Numbers: A Breakdown Of How Flooding Disproportionately Affects The Poor Globally, And At Home.

May 4th, 2019 | Updated June 29th, 2020

by Alexander Fella | alex@theurcnorfolk.com

The coastlands have seen, and are afraid

- Isaiah 41:5

When

Isaiah, speaking on behalf of God, tells the Israelites that God will “open rivers” for the “poor and needy,” he may have gotten more than he bargained for. Around the world, it’s often the meekest of the Earth that inherit the burden of flooding more than anyone else. From Mumbai, to New Orleans, to Norfolk, the poor routinely endure the burden of flooding while also being the least responsible for it. Even years after a major storm, low-income communities routinely face the consequences of flooding while the affluent do not.

Flooding in Norfolk, Virginia. 1933. | Virginian-pilot

There are a few claims here that need parsing. One, is that the poor suffer from floods disproportionately to the wealthy. The other is that the poor are the least responsible for flooding compared to their rich counterparts. Let’s start with the first line of reasoning, that the poor are the least responsible for flooding. It’s an odd claim to make on the face of it. Flooding has existed since, well, at least recorded history. Floods play a central role in Abrahamic, Sumerian, Mesopotamian, and Native American creation tales. Floods by their very nature precede class. So how can class have anything to say about floods? In the ancient Near East, it was the rich and powerful Babylonians who harnessed their annual floods for profit, while the poor Canaanites suffered the water’s destructive powers. Today, not a whole lot has changed. The rich and powerful are still largely resilient to flood damage, and they’re poised to make a healthy profit off those who are not. Only now, the poor continue to suffer at the hands of hurricanes, rising sea levels, and rainfall while being the least responsible for them. So if floods, and their world-ending consequences, have existed for so long then how does class play a role? And what does it mean to be responsible for a flood?

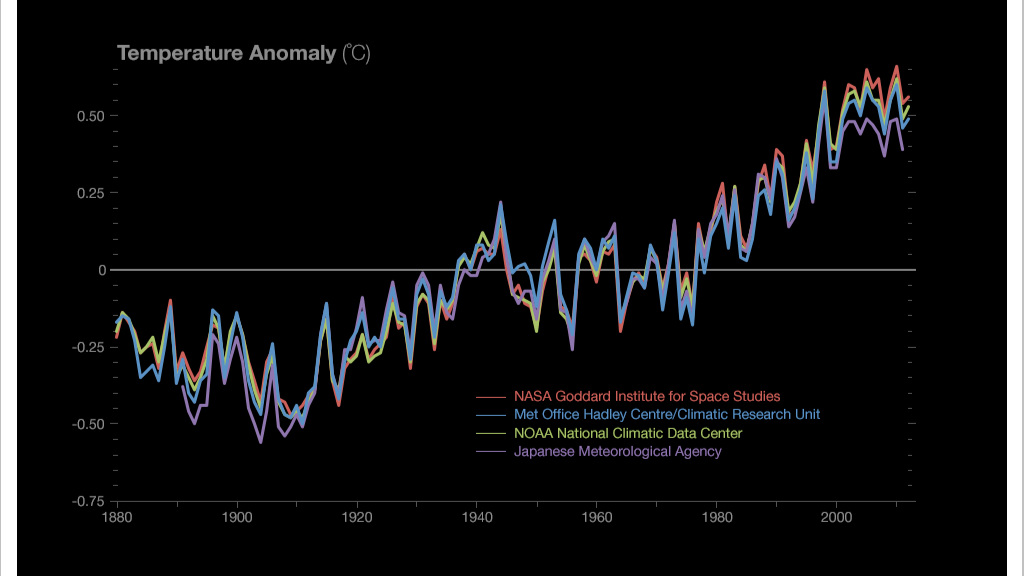

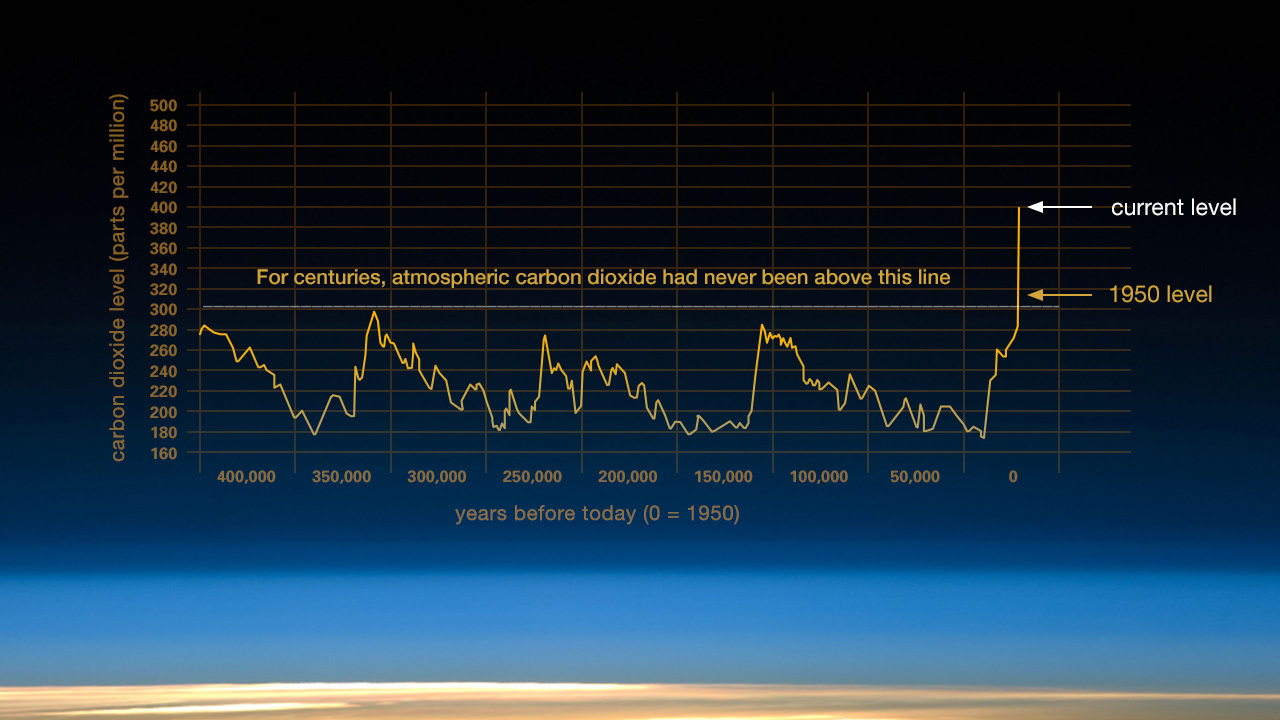

First, let’s get clear on a few basics. The basic climate calculus goes something like this: collectively, the largest producers of carbon emissions are the wealthiest people on the planet. When carbon, a greenhouse gas, is released, it traps heat from the Sun closer to the Earth. This causes the Earth’s temperature to increase. [1] [2] [3] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] The scientific literature surrounding this process is quite solid. As the Earth’s temperature increases, the surface temperature of Earth’s oceans increases. As the surface temperature of Earth’s oceans increases, there are a number of compounding effects that change our oceans and weather patterns. Warmer oceans increase the frequency at which hurricanes are generated. Warmer oceans also generate hurricanes with more precipitation and stronger winds. Put simply, warmer oceans create more, and stronger, hurricanes. Hurricanes, in turn, cause flooding. As with all things climate-related, nothing occurs in a vacuum. An increase in stronger hurricanes is compounded with rising sea levels. As the planet’s oceans warm, they melt ice-sheets and glaciers, and since things expand when warm and contract when cold- rising temperatures also contribute to an expanding sea, increasing the threat to coastal communities.

Oxfam

So, warmer oceans, hurricanes with greater precipitation, and rising sea levels increase the occurrence and severity of flooding. Now comes the question I raised at the outset, who is responsible for producing all these greenhouses gases? In a recent study, Oxfam noted that the richest 10 percent of the world’s population produce nearly half of the world’s total carbon emissions. Unsurprisingly, China and the United States place first and second respectively on the list as the world’s largest carbon emitters. Adjusted for all greenhouses gasses (not just man-made carbon but also natural productions of methane from livestock), China and the United States still place first and second, respectively, by a long shot. What does it take to count as the richest 10 percent in the world? About $93,000, including property value. And while China may have the United States beat on total greenhouse gas emissions, the per capita numbers skew slightly different. The poorest half of China’s population, roughly 600 million people, only produce a meager one-third the amount of carbon that America’s richest 10 percent produce. If you live in the United States, and are worth more than $93,000, it’s very likely you’re responsible for producing a significant portion of the world’s greenhouse gasses.

What’s behind those numbers? A lot of it comes down to lifestyle, especially if you have a net worth of more than $93,000. But before you start reaching for your canvas tote, you should know a “green lifestyle,” (measured only by the length of a Fresh Market bill) makes little difference in global carbon emissions. In fact, well off Americans who identify as eco-friendly actually leave a greater carbon footprint than their lower-income counterparts. Why? Because the greatest contributors to one’s carbon emissions are “per capita living space, energy used for household appliances…car use, and vacation travel.” Recycling or energy efficient appliances are not enough to offset the carbon cost of electricity if you live in 3,000 sq. ft home with a half-acre yard. What’s more, the diet of the world’s wealthy has a significant role in carbon production. The consumption of animals and their byproducts contributes to about 15% of the world’s greenhouse gas production. As Julia Moskin, et al. recently published, meat and dairy alone contribute about as much greenhouse gas as the emissions “from cars, trucks, airplanes and ships combined in the world today.”

So far we’ve briefly laid out how a warming ocean contributes to the conditions for flooding. We’ve also noted how the lifestyle of the world’s wealthiest people accounts for a significant portion of greenhouse gasses warming the Earth, while the global poor contribute very little to the production of greenhouse gasses comparatively. Now comes the more slippery claim to parse out: how do the poor disproportionately suffer from flooding compared to the rich?

India is a good place to start here. India places third highest on the list of countries producing greenhouse gases. However, even the wealthiest 10% of Indians produce about the same amount of carbon as the poorest 20% of Americans. As Oxfam further notes “the emissions of someone in the poorest half of the Indian population are on average just one-twentieth those of someone in the poorest half of the US population.” At the same time, India’s poor are particularly vulnerable to the effects of America’s carbon production, as they face flooding, rising sea levels, and strong cyclones (hurricanes, but with a different name).

One does not have to look far for the evidence of how the poor bear the burden of flooding in India while being the least responsible for it. On August 29th, 2017 torrential rains fell on Mumbai. 10 inches in 12 hours. In Mumbai, half the population lives in jhoppad pattis, or shanty lean-to housing. When the rains hit Mumbai, entire communities of these homes were swept away, including Suraj Dhurve’s home. Dhurve, and around 50 other families were living underneath an overpass before the floods hit, washing away their homes and killing 15. With little options to move, many of these families will continue to face stronger flooding and worse rains. “We don’t even have a dream of where we would go,” said Dhurve. Mumbai’s flooding comes just days after flooding occurred south of Mumbai in Kerala, killing 324 and displacing 800,000, adding to 2017’s death toll of over 1000 from flooding in South East Asia. Those primarily affected in Kerala were the poor who lived in similar lean-to homes, or in rural areas with mud-brick houses who relied on subsistence farms that are now underwater.

“Suraj and Babli Dhurve with their chldren in their shelter in Mumbai. Every summer when the monsoon hits, the family’s home is flooded.” (Atul Loke | The New York Time)

In 2017, each rainstorm to hit India brought with it fears and memories from 2005. Wherein 500 people lost their lives and hundreds of thousands lost their homes after Mumbai received 38 inches of rain in one day. A key point here is that while the summer monsoon season in India typically brings heavy rain over a sustained period of months, the Indian Meteorological Association has noted a spike in extreme weather events in India over the past 19 years, calling 2000 a “tipping point,” with Mumbai’s average highest temperature rising 1.6 degree Celsius since recording began. There is a strong correlation between the warming of Indian oceans and an increase in extreme rainfall. Keep in mind here that India produces only a fraction of the carbon that the world’s wealthiest people produce, and India’s impoverished are also dangerously vulnerable to flooding as a result of a warming planet.

Tipping the Carbon Calculus

The case of flooding in India offers a clear picture of how those least responsible for environmental destruction bear the brunt of the climate’s extreme weather. India presents a more straightforward calculus of how those least responsible for carbon production, suffer the effects the most. As noted above, the wealthiest 10% in India produce about the same amount of carbon as the poorest 20% of Americans. And the poorest half of India only contribute one-twentieth of someone in the poorest half of the United States. It’s fair to say India’s poor disproportionately suffer the effects of worsening floods as a result of the average American’s carbon footprint. So if the calculus between responsibility and devastation is clear between America and India, what happens when the floods hit closer to home in, say, Houston? Or New Orleans?

While India suffered devastating floods in 2005 and 2017, these years also gave us historic flooding in the United States. Clearly, the calculus changes a bit here. The poor in America know a level of wealth that is far beyond what the poor in, say, India experience. However, America’s poor still suffer from flooding in disproportionate ways compared to the wealthy. Take what is probably America’s most well-known flood, the one accompanying Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

When Katrina made landfall in New Orleans, the flooding was not spread evenly throughout the city. 400,000 residents fled New Orleans, but the affluent Uptown and French Quarter districts of New Orleans were largely spared serious flooding. The predominantly black and impoverished New Orleans neighborhoods were not so lucky.

New York Times

In particular, flooding hit New Orleans’ low lying Lower Ninth Ward hardest, where the average resident was making about $16,000 a year. Preemptive strategies, especially in 2005, often fail those who do not have access to reliable transportation for an evacuation, nor a cell phone to made aware of how serious the impending threat is. Furthermore, when flooding hits areas like the Lower Ninth, low-income housing can rarely stand up to force of the water. When the Industrial Canal levee gave way on the West bank of the Lower Ninth, some homes were lifted clean off their foundation as the Lower Ninth sat under 10 feet of water. Sure, insurance can prove a viable safeguard when the State’s protective infrastructure fails, however, low-income homeowners are often priced out of that safety net. Averaging about $700 a month, flood insurance is out of reach for families already struggling to make ends meet.

“Katrina’s floodwaters overwhelmed a levee in the Industrial Canal and spilled into the Lower Ninth Ward.” (Vincent Laforet | The New York Times)

And while the immediate devastation from flooding can be captured and broadcast on television sets, it often takes years for the more insidious damage of a flood to surface. Or in the case of the Lower Ninth, it took years to reveal that the flood’s damage remained stagnant. According to the Louisiana-based research Data Center, a decade after Katrina more than half the neighborhoods in New Orleans have recovered 90 percent or more of their population lost to Katrina. This has not been the case for the Lower Ninth. While surveying the damage to the Lower Ninth from a Blackhawk helicopter, the city’s then-head of Homeland Security Col. Terry J. Ebbert said “there's nothing out there that can be saved at all.” And slow to save the Lower Ninth New Orleans was. The Lower Ninth was the last part of the city to be drained, the last to have electricity restored, and 6 months after the affluent neighborhoods received FEMA shelters, the Lower Ninth was only starting to receive their temporary homes. Though Ebbert is no Isaiah, over a decade later his prophecy holds true. Only 37% of households returned to the neighborhood. Schools were never reopened, businesses are only starting to return. Today, in many parts the Lower Ninth looks like it did shortly after Hurricane Katrina.

Much of New Orleans’ Lower Ninth remains unrepaired since the flooding

What’s more, the ramifications from Katrina’s diaspora have ushered in a city gentrified by flooding. Pre-flood, the city was more than two-thirds black, with about a 25 percent white population. Today, the percentage of white residents has increased to 30 percent, while black residents dipped below 60 percent. This fulfills another prophecy from George Bush’s then-HUD director Alphonso Jackson: "New Orleans is not going to be as black as it was for a long time, if ever again,” no doubt in part because Jackson advised “it would be a mistake to rebuild the Ninth Ward.” As Columbia professor John Mutter, author of The Disaster Profiteers: How Natural Disasters Make the Rich Richer and the Poor Even Poorer, notes succinctly “The rich can survive well, and the poor don't.” And when it comes to flooding, the rich recover well, and the poor don’t. Though occurring over a decade ago, flooding in New Orleans is worth spending so much time on, because it offers stark context to the long-term effect flooding has on poor communities. Particularly, Katrina shows us how the poor suffer most when the flood hits, and long after the waters recede.

A major factor in establishing that impoverished people suffer flooding disproportionately to wealthy folks is the concentration of low-income residents in flood-prone areas. New Orleans is not alone in its urban setup. In 2017, when Hurricane Harvey flooded Houston, the city’s low-income residents were primarily living in densely populated flood corridors (unlike flood plains, corridors are expressly built to flood in order to protect other parts of the city). As Oxfam further notes in its “Carbon Inequality” study, “when Superstorm Sandy hit New York in 2012, 33% of individuals in the storm surge area lived in government-assisted housing, with half of the 40,000 public housing residents of the city displaced.” Indeed, across the country some 450,000 government subsidized homes are in flood prone-areas. And Norfolk, Virginia has its fair share of those flood-prone homes.

Norfolk's Flooding

Norfolk is home to 1,700 public housing units spread over three neighborhoods and 20 acres. Every single one of these homes is in a flood zone. These three neighborhoods, Tidewater Gardens, Calvert Square, and Young Terrace, compose the ‘St. Paul’s Quadrant’, all prone to severe flooding. Each new storm to hit Norfolk raises memories of previous floods. “Flooding, rain, just to hear those words, for parents it puts a heavy burden on them," said Michelle Cook, a St. Paul’s resident. And that burden is only increasing. Norfolk has “experienced twice as many instances of tidal flooding in the past two decades, as it had in the previous three decades.” And with a warming climate, Norfolk is simultaneously experiencing an increase in heavy rains. To make matters worse, Norfolk also has one of the fastest rising sea levels in the country, half a foot since 1992. The global average is around 2.6 inches. With fears sufficiently (and a bit ironically) stoked by Fannie Mae about a flood-induced mortgage crisis, and from Moody’s about a possible hit to Norfolk’s credit rating, the city has acted. A city-wide plan will rezone some middle-class neighborhoods and rural areas as too far gone to be saved, and other neighborhoods like St. Paul’s will get a complete overhaul.

“A passerby stands in the median and looks over the flooded underpass on Virginia Beach Blvd. near Tidewater Drive in Norfolk on Sunday, Oct. 9, 2016.” (Bill Tiernan | The Virginian-Pilot)

As we’ve noted above, flooding can destroy low-income housing, and permanently displace black communities. In order to Fortify the St. Paul’s area against flooding, Norfolk will demolish its 1,700 public housing units in order to build a mixed-use mixed-income flood resistant neighborhood. With 1,700 low-income families losing their homes, slim offerings for Section 8 housing in Norfolk, and a long waitlist for already full public housing, the primarily black community of St. Paul’s will be dispersed out of Norfolk. In order to save the poor community of St. Paul’s from flooding, the city will tear it down. Though promises have been made that current residents may return to St. Paul’s, only 600 units have been set aside for low-income housing. The Mayor’s Advisory Committee has made it clear, staying in Norfolk will not be an option for everyone. “We want to make sure what we’re not doing is reconcentrating people into poorer neighborhoods,” Councilwoman Angela Williams Graves said. If floods can threaten destruction and displacement of low-income homes, so can attempts to stop that flooding.

Though the St. Paul’s renovation project has been billed as a gateway for upward social mobility, flooding has long been the impetus for renovating St. Paul’s Quadrant. By one planer’s account “St. Paul’s will be the transformation of the low-lands area that is often devastated by flooding into a water eco-center comprised of great parks and green spaces…Norfolk will no longer be on the water but rather will be of the water." Such a transformation comes with a heavy toll on the impoverished black community living in St. Paul’s. The first round of 120-day notices have been issued to begin moving out, and there remains a lot of uncertainty about where residents will move to. "Hello, excuse me,” Cook said, “Everybody needs housing. It just don't make any sense to me to say you're going to tear down housing and not replace what you take down." With little options, St. Paul’s residents, already suffering from flooding may end up in other flood-prone areas around the Hampton Roads area.

Whether out of sheer necessity as Norfolk’s Planning Director has stated, or a subtle attempt at city-sponsored gentrification as others have raised, one thing is for sure: there’s a profit to be made. The entire St. Paul’s area is housed in an Economic Tax Opportunity zone, capital investments made on the front end now will be tax-free in a decade’s time. As major financial institutions begin investing to rebuild St. Paul’s, tax-exempt capital gains promise a healthy profit while the St. Paul’s community is displaced. The point here is that in Norfolk’s preemptive plan to solve flooding, they will simply recreate the effects of a devastating flood. Though this time the flood comes with a pen and a bulldozer rather than storms and rainwater. And with the wealthy set to make a profit off the flood-proof renovation, the poor continue to suffer the effects of flooding disproportionately to the rich. In the examples above, the poor suffered the flooding disproportionately after the water came. In Norfolk, the poor are suffering before the flood even hits.

From South East Asia to the Gulf Coast, and the Chesapeake Bay- the coastlands have seen, and are afraid. And for the poorest among us, rightly so.

Alexander Fella, alex@theurcnorfolk.com